Coal power plant dispute: positives, negatives of energy producers

Written by: Ella Abbott, Adriona Murphy and Ray Padilla

I.

Along the Ohio River, where Ohio meets West Virginia, lies the tiny village of Stratton.

Stratton sits in Jefferson County;the city’s population is less than 300. Due north of the city, the residences live near a huge chimney that can be seen from miles away. Below the chimney is the W. H. Sammis Power Plant.

The power plant is supposed to close in the coming years, leaving many to contemplate what the effects will be — both financially and environmentally.

Stratton Chief of Police Mike Wilson and Jefferson County Sheriff Fred Abdalla don’t want to see the plant close.

FirstEnergy Solutions, which owns the plant, announced in August it would be deactivating four coal- and oil-fired power plants, including the Sammis plant.

One part of the plant burns oil and the other burns coal. It’s FirstEnergy’s largest coal-fired power plant in Ohio, according to the company’s Sammis plant fact sheet.

In Steubenville, twenty minutes south of Stratton, Mayor Jerry Barilla said he understood that the plant’s closing is good for the environment, but he still couldn’t say it is a good thing himself.

For people in cities like Stratton and Steubenville, plants and factories are a part of the towns. Wilson and Abdalla share a sense of disbelief the plant will actually close, but worry that when it does, it could fundamentally change the village of Stratton.

II

FirstEnergy announced the plant closures via a press release on Aug. 29, 2018.

“(FirstEnergy Solutions) is closing the plants due to a market environment that fails to adequately compensate generators for the resiliency and fuel-security attributes that the plants provide,” it said.

The other plants facing deactivation are the Eastlake 6 plant in Eastlake, OH and the Bruce Mansfield Units 1-3 in Shippingport, PA.

The plants aren’t due to close until 2021 or 2022, depending on the unit, and they will continue normal operations until then, according to the press release.

It’s a far cry from where the coal industry used to be in the state.

III

The history and influence of the coal industry runs deep in Ohio. So deep, in fact, no one knows the date when it was first mined here. According to the Ohio Coal Association, one of the first mentions of coal in Ohio was in 1748 near Bolivar in Tuscarawas County. Mining was first reported in 1800, before Ohio was even a state. Since 1800, more than 3 billion tons of coal have been mined here.

The use of coal has steadily increased over the years as it began to replace wood as the most common source of fuel in homes and small factories. The introduction of the railroad and advances in machinery continued to boost the coal industry and soon the coal-fired electric-generating plant was introduced. In 1883, The Tiffin Edison Electric Illuminating Company was built — making it the tenth power plant in the United States, and the first in Ohio.

From there, coal became a primary source of energy for Ohio and many of the surrounding states, including Pennsylvania. The combination of the accessibility, the economic shift of the state from agriculture to manufacturing and advances in transportation, allowed for Ohio to develop both a thriving industry as well as a dependence. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Ohio is still one of the top five coal-consuming states. The EIA also said almost three times as much coal is consumed in Ohio as is produced there and 90 percent of the coal consumed in the state is for electric power. Ohio is the 13th largest coal producer in the United States and two-fifths of the coal produced here is transported to other states. While the midwest is primarily dependent on coal, southern and western states heavily use natural gas. The east coast is more varied, using renewable resources, natural gas, nuclear power, hydroelectric power and biomass.

The total number of coal-fired power plants dwindled over the years as stricter regulations from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) went into effect. The bituminous coal produced and burned in Ohio has higher levels of sulfur, the exact element these regulations are seeking to reduce.

IV

New technology has created stricture regulations, the U.S. EPA controls the amount of emissions each plant is allowed into the air, which contributes to air pollution. Advancements in energy technology makes it easier for regulatory agencies, including the Ohio EPA, to lower the regulations.

In 1963, the U.S. Congress passed the Clean Air Act, which regulates air quality at the national level. The law requires the U.S. EPA to be responsible for protecting and improving the nation’s air quality and the stratospheric ozone layer — the upper layer of the ozone. Currently, Ohio’s Division of Air Pollution Control (DAPC) is responsible for regulating air quality in the state with the goal of protecting public health and the environment.

In a January press release, the U.S. EPA withdrew its “once in, always in” policy for “major sources” of hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act. This means if any factory emitting air pollution reduces its emissions, it could be reclassified from a “major source” to an “area source.” “Major sources” are defined as places that emit 10 tons of any hazardous air pollutant per year.

The state DAPC operates in nine local air agencies to monitor sites that collect air quality data. There are over 120 monitoring sites in Ohio that sample the air hourly or intermittently on a 24-hour basis.

The major pollutants coming from coal-fired power plants include carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). Each is monitored by the companies themselves and the Ohio EPA.

CO is a colorless, odorless gas that can easily go undetected and cause poisoning. The Centers for Disease Control and Protection says “the most common symptoms of CO poisoning are headaches, dizziness, weakness, upset stomach, vomiting, chest pain and confusion.” It’s formed when carbon does not burn correctly and can be created when burning fuel.

NO2 is another result of the burning of fossil fuels and can irritate a person’s airways and exposures over short periods can aggravate respiratory diseases. The U.S. EPA says it can lead to hospital admissions and emergency room visits. Longer exposures can contribute to asthma developments.

SO2 contributes to acid rain, which led to regulations on coal-fired power plants like scrubbers and coal washing. It’s also created when fossil fuels are burned.

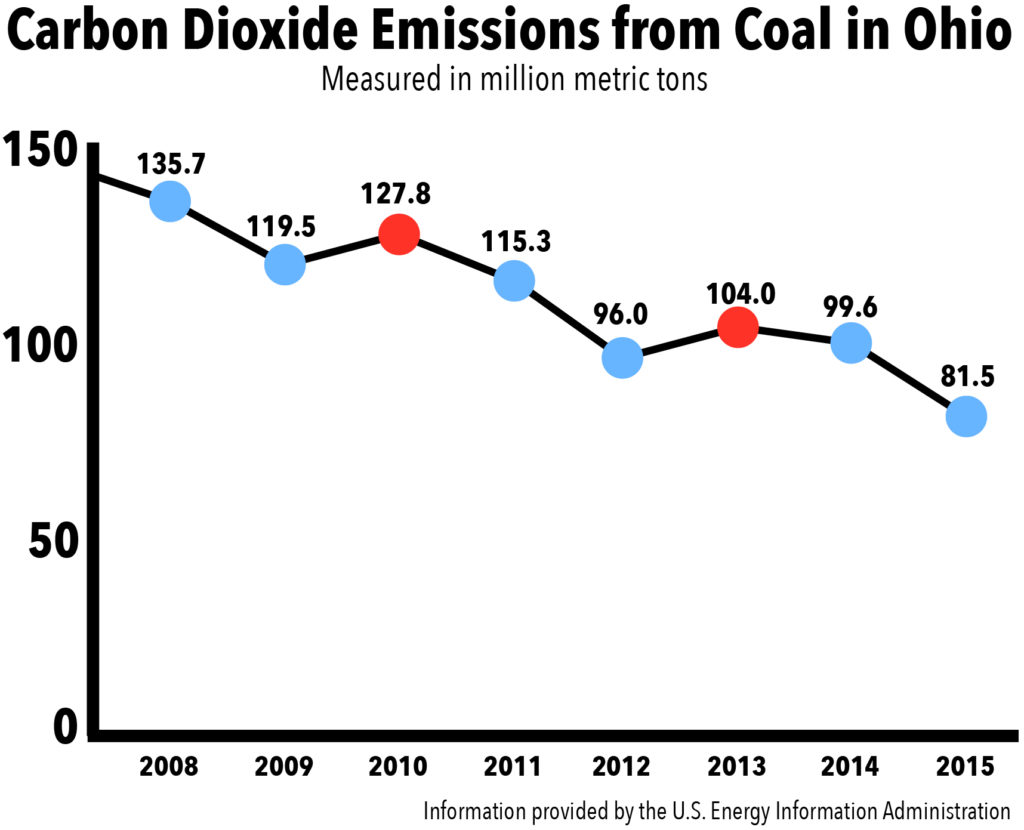

Within Ohio, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels from coal decreased 42.8 percent between the years of 1980 to 2015, according to the EIA.

In Jefferson County, where the Sammis plant is located, the Ohio EPA controls all of the air authority, said Marc Maragos, the director of environmental health in the county. He said his department works hand and hand with the EPA and if there are new regulations, they will be implemented in the county. His agency doesn’t track the emissions specifically produced in the county.

The EPA and local agencies track the quality of the air and create an “Air Quality Index” which is used to create a current air quality map for the state. This enables residents in Ohio to understand if the air they breathe is clean, unhealthy or hazardous.

By tracking the air quality, the Ohio EPA is able to create forecasts to provide information to the public about pollutants in the air and how it’s associated with their health.

V

Within the Air Quality Index Forecast on the Ohio EPA website, it explains how people can protect themselves from high levels of pollutants. It says when people exercise or perform other strenuous activities, they increase their breathing rate and take in more pollutants.

Laura Kate Bender, the national director of advocacy for the American Lung Association, said coal-fired power plants are huge contributors to health problems in humans.

She plants, like the one in Stratton, produce particle pollutants, which are a mixture of solids and liquid droplets floating in the air.

“Particle pollution can cause asthma attacks for people with asthma, it could cause lung and heart problems, it could actually cause lung cancer,” Bender said. “And it adds up to hospitalizations and missed days at work and school and premature deaths.”

While those effects directly impact people living near coal-fired power plants, she said particle pollutants can travel hundreds of miles away from the source.

In Stratton village, we noticed most of the people were over 40. According to the United States Census Bureau, there is estimated to be more than 50 percent of residents who are 65 years or older. The people living in the village seemed unaware of the health effects caused by the plant less than 50 feet away from them.

“Anyone can suffer health effects from these emissions, but certain categories of people are particularly vulnerable,” Bender said. “That does include seniors. It also includes kids, babies, pregnant women and people who already have lung and heart disease(s).”

VI

While the closures seem like an easy win for the environment and health for communities, they could have heavy consequences for the county where they’re located.

In Stratton, on a sunny day in September, life continues as the plant looms overhead. There’s a playground at the center of town, tucked in behind the fire station. Children ride their bikes along the streets and a couple takes photos on their porch before the high school’s homecoming dance.

For this town, the effect of the W.H. Sammis plant closing could be life-altering.

The plant pays $7 million annually in property taxes. It’s the largest taxpayer in Jefferson County, according to FirstEnergy’s fact sheet. Fifty-two percent of those taxes go toward the local school district. Steubenville City Councilwoman Kimberly Hahn said the loss of that money could greatly affect the school.

“The impact is gonna be pretty great on the Edison Local High School, which is in more of the Toronto area (north of Stratton), but it’s the high school that students from Stratton would go to,” Hahn said.

The loss of the plant won’t affect only Stratton, but people from all over the county. The Sammis plant employs about 400 people, according to FirstEnergy.

“I try to tell my children when we smell that from the steel mill across the river ‘that’s the smell of jobs,’” Hahn said. “We need to be grateful that people have work.”

Hahn said she hasn’t heard complaints from residents about the plant or its health effects herself.

Barilla, the Steubenville mayor, reflected on his city’s past. It used to be home to a coal mine situated downtown. The mine pulled coal from the earth and ground it up in preparation to be sent to the Sammis plant.

“Every morning, you’d have this black soot on the sidewalks. Everywhere, you’d have this little glittering of sparkles in it,” he said. “And so, every shop owner and housekeeper, the front porches, the streets all had to be swept on a daily basis.”

“We lived under that,” Barilla said. “People did live back then, they did live into their eighties, some maybe into their nineties.”

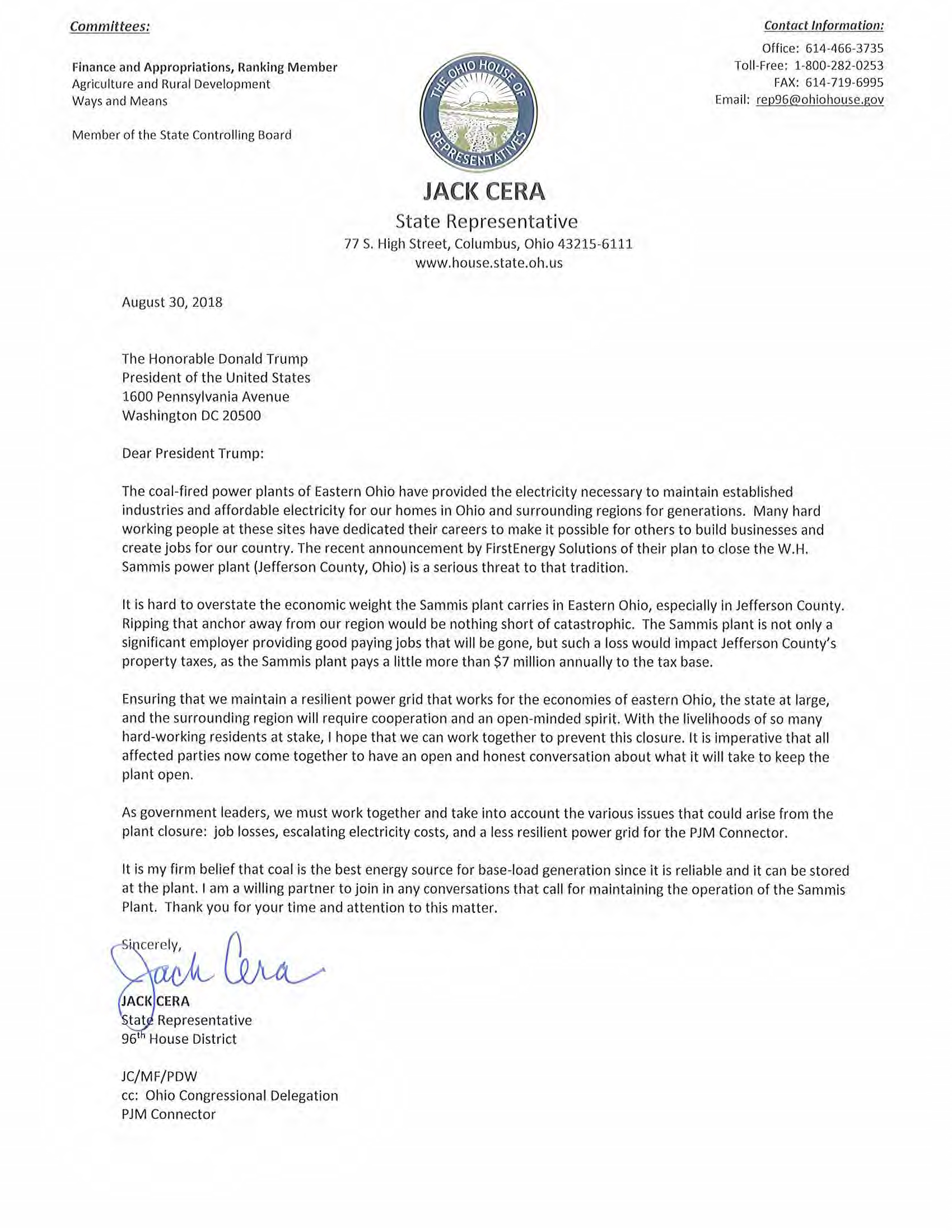

In September, Jack Cera, the Ohio House representative from Bellaire, wrote a letter to President Donald Trump and Governor John Kasich and asked for help to keep the Sammis plant open. In the letter, Cera urges for a different solution to be found.

“With the livelihood of so many hard-working residents at stake, I hope that we can work together to prevent this closure,” Cera writes. “It is imperative that all affected parties now come together to have an open and honest conversation about what it will take to keep the plant open.”

In Stratton, the consequences of the plant being shut down aren’t lost.

“It’ll be devastating,” Abdalla said, as he continued to work on his yard.

Contact Ella Abbott at dabbott9@kent.edu,

Adriona Murphy at amurph30@kent.edu

and Ray Padilla at rpadill2@kent.edu.