A hazardous wasteland called home

East Liverpool residents’ concerns still

high after 2013 incinerator explosion

Written by Cameron Hoover, Adam Kirasic and Valerie Royzman

Richard Copeland is a lifelong East Liverpool, Ohio, resident whose house is located on St. George Street about two blocks from the Heritage Thermal Services facility, a historically contentious hazardous waste incinerator in town.

Upon mention of the incinerator, Copeland and a woman he was speaking with on his front porch lamented the facility as an eyesore. “Imagine looking out your window and seeing that ugly-ass thing,” the woman said, pointing to the smokestack rising in the distance billowing white plumes. Without citing specific facts or figures, Copeland said he worries about the potential health effects caused by the waste the facility incinerates.

“A few years ago, (the incinerator) spewed black shit all over the neighborhood and all over the cars,” Copeland said. “My mom’s was one of them. She was on the news and everything.”

One afternoon in July 2013, the incinerator exploded, sending 800 pounds of potentially hazardous ash — the “black shit” Copeland was referring to — into the air, which settled in the neighborhoods surrounding the plant.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, hazardous waste “is a waste with properties that make it dangerous or capable of having a harmful effect on human health or the environment.”

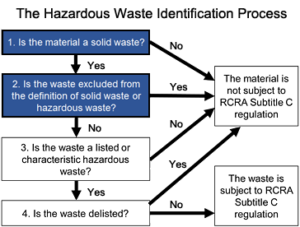

Hazardous waste exists in the form of liquids, solids and gases and comes from a variety of sources, such as industrial manufacturing and batteries. The EPA outlined hazardous waste regulations that define which materials actually qualify.

First, it must start in the form of solid waste. Next, those who generate the waste need to determine “whether or not the waste is specifically excluded from regulation as a solid or hazardous waste.”

Once those seeking to rid themselves of the waste know for certain their waste is solid, they must find out “whether or not the waste is a listed or characteristic hazardous waste.”

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is the public law that provides the framework for waste generators to properly manage hazardous and nonhazardous solid waste. The U.S. EPA created the Cradle-to-Grave Waste Management Program to handle hazardous waste safely “from the time it is created, while it is transported, treated, and stored, and until it is disposed.”

The Heritage Thermal incinerator burns 60,000 tons of waste every year in a large kiln set to 1,800 degrees, turning waste that’s too toxic for landfills into smoke and ash, former Heritage Thermal President John Avdellas told The Business Journal in Youngstown. The day of the 2013 explosion, the plant was burning waste sent from an oil refinery in Toledo.

Heritage Thermal notified residents of the industrial accident and went door to door offering to replace vegetable gardens and wash people’s houses and pools where some of the ash landed.

It took Heritage Thermal several weeks to comply after EPA investigators sent the company a Section 114(a) request, which gives the administrator the right to ask for information, on the explosion in regard to compliance with the Clean Air Act.

Once the company responded, it also admitted to a series of issues that happened when the incinerator reached dangerous levels of pressure. Heritage had a similar incident in December 2011 due to overpressurization in the incinerator.

The EPA sent Heritage Thermal a letter in March 2015, which said the company had nearly 200 violations — operator or mechanical errors — over the previous four years.

A report from Cox-Colvin & Associates, Inc. Environmental Services, a consultant based in Plain City, Ohio, found a sample of the ash contained arsenic, lead and manganese. When consumed in small amounts over a long period of time, these chemicals can cause serious illnesses, including various cancers, and prolonged death.

Multiple attempts to contact Heritage Thermal and Ohio EPA representatives — via phone, email and in-person visitations — were either not returned at all or in a timely manner. Reporters who went to the facility were directed “down the hallway to the right” to public relations specialist Raymond Wayne’s office, but the only thing down the hallway were dimly lit empty rooms, a supply/electrical closet and a restroom.

East Liverpool is notorious for having a significantly higher cancer rate (615.8 cases per 100,000 population) than the rest of Ohio (450.4 cases per 100,000 population), according to data compiled by the Ohio Department of Health. In Columbiana County, home to East Liverpool, 28.5 percent of cancer-related deaths between 2010 and 2014 were caused by lung and bronchus-related diseases.

The town’s residents had to decide which was more important to them: jobs or potential adverse health effects. Years later, Copeland has made up his mind.

“It might’ve created jobs back then, back in the ‘90s,” he said. “But now? Now the health effects aren’t worth it.”

The chemicals created when hazardous waste is burned have been linked to cancers, higher rates of miscarriages and early death. While Heritage Thermal can’t be specifically linked to these statistics, these chemicals are burned by the incinerator in East Liverpool, and residents tend to be more skeptical because of the area’s infamous health issues.

The residents of East Liverpool have debated the incinerator since its inception nearly 25 years ago, and the debate only grows hotter when one considers the facility was built blocks away from both East Elementary School and Willie Cook Memorial Park, a local playground frequented by children. Less than a half-mile away is Casa De Emanuel, a popular Italian restaurant.

The histories of the elementary school and the incinerator are intertwined. Al Gore, whose 2000 presidential campaign centered around environmental issues, was maligned by local political and environmental activists for his failure to shut down the incinerator.

In October 2000, East Liverpool resident Alonzo Spencer claimed to the Warren Tribune Chronicle during a campaign visit by Gore that smoke from the incinerator regularly blew into the doors and windows of the school.

Sandy Estell, who lived at 1410 Etruria St. between East Elementary School and the incinerator, told the East Liverpool Review in 2004 her windows shook and she needed to rush her kids back into her house when a fireball escaped the facility into the air, sending smoke through the neighborhood. The elementary school was shut down two years later in the interest of the safety of the attendees and after years of complaints from students’ parents.

Carl Pearson lives across the street from Copeland and spent 26 years in East Liverpool. His children grew up in the city and attended East Elementary.

“At first, I was upset about it because we didn’t know what it was going to be like or anything,” Pearson said about the incinerator as his wife, Theresa, bounced their infant granddaughter on her knee.

“It was supposed to bring a lot of business, but it hasn’t done anything, as far as I know. It killed the school up there,” he said, pointing in the general direction of where the elementary used to stand.

Tim Brooks, a historian at the East Liverpool Historical Society’s Thompson House, said some residents were hopeful for new job opportunities after it was announced about 25 years ago there was going to be a hazardous waste incinerator in town.

“It depends on who you talked to,” Brooks said. “There was always a group of people very strongly opposed to it. I was a little young at the time to have a voice, but there were a lot of businesspeople in the chamber of commerce who I remember talking about it, like, ‘Well, the potteries aren’t coming back. We need something.’”

Brooks said he believes this sentiment was borne more out of desperation than carefully considered fact. The city lost thousands of jobs in the manufacturing and pottery industries over the last 100 years. This had an effect on the health — both mental and physical — of its residents, Brooks said.

Heritage Thermal Services video

According to countyhealthrankings.org, Columbiana County has fewer people with college educations, a higher unemployment rate and a higher percentage of children in poverty compared to averages across the state. The county also has higher levels of air pollution via particulate matters and more drinking water violations than state averages.

Brooks worries East Liverpool may go by the wayside if this doesn’t change.

“It really is a problem here,” Brooks said. “Almost no one’s children stay here. There’s really not much reason to. My daughter left and lives up in Stow now. Economically, there’s not much to anchor people to the area. … The city was desperate for a business that would pay respectable wages.”

Even today, with residents like Copeland and Pearson unhappy with the incinerator and the handling of the 2013 explosion that left much of the surrounding area shrouded in ash, the federal government still hasn’t clamped down on the facility after years of mispractice.

The New York Times reported in December 2017 “the EPA has not moved to punish the plant’s owner” since Donald Trump became president, “even after extensive evidence was assembled during the Obama administration that the plant had repeatedly, and illegally, released harmful pollutants into the air,” over several years, including the 2013 explosion.

The Trump administration is holding polluters — like those in East Liverpool — less accountable for environmental regulations compared to the last two administrations, both Democratic and Republican, according to an analysis of enforcement data by The New York Times.

“The Times built a database of civil cases filed at the E.P.A. during the Trump, Obama and Bush administrations,” the article said. “During the first nine months under Mr. (Scott) Pruitt’s leadership, the EPA started about 1,900 cases, about one-third fewer than the number under President Barack Obama’s first E.P.A. director and about one-quarter fewer than under President George W. Bush’s over the same time period.”

Brooks said the people who were against the incinerator being built 25 years ago are still against it today.

“Not a lot of people are like, ‘Gee, I’m sure glad this incinerator is here,’” he said. “But not many are joining the other side either.”

Contact Cameron Hoover at choove14@kent.edu.

Contact Adam Kirasic at akirasic@kent.edu.

Contact Valerie Royzman at vroyzman@kent.edu.